| Entries |

| P |

|

Prohibition and Temperance

|

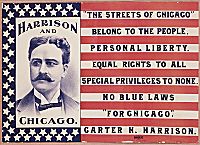

Organized expression of temperance ideas first appeared in Chicago in 1833 with the Chicago Temperance Society, a branch of the American Temperance Society, which attracted 120 members within a year. By 1847 Chicago had two Washington Temperance Societies, three tents of the Independent Order of Rechabites, three divisions of the Sons of Temperance, the Chicago Bethel (seaman's) Temperance Society, and the Catholic Benevolent Temperance Society.

|

Concern about the rising consumption of beer in the county generally, and in the city in particular, re-energized temperance work in Chicago immediately after the Civil War. In the 1870s and 1880s a number of new organizations appeared, including the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Citizens' League of Chicago for the Suppression of the Sale of Liquor to Minors. While both sought liquor law enforcement, the WCTU also pursued prohibitionist goals along with providing social services that highlighted the problems women particularly faced from male intemperance. By 1889 the Chicago Central WCTU had established day care centers for children of working women, a medical dispensary, kindergartens and Sunday Schools, lodging houses, and a low-cost restaurant, and had organized branches around the city and in the suburbs. New Roman Catholic organizations, such as Erin's Hope Temperance and Benevolent Society and the Catholic Total Abstinence Union (CTAU), also organized in Chicago in this period. They pursued moral suasion and social-reform agendas but were not necessarily prohibitionist.

In 1898 the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), a group of Protestant clergy and laypeople (most of whom were men) committed to eradicating saloons and liquor traffic from the United States, organized in Illinois and by April 1900 claimed 18,000 members in 12 counties including metropolitan Chicago. Unlike the WCTU or the CTAU, the ASL's first agenda was the election of dry candidates. Aided by a sharp national increase in beer consumption between 1900 and 1913, their single-issue focus and pressure-politics approach worked: in 1907 the general assembly passed a local option bill sponsored by the ASL that dried up two-thirds of Chicago precincts by 1909. In 1919 Illinois lawmakers ratified the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, making the manufacture, sale, and transport of alcohol illegal in the state.

|

Alcohol consumption in the United States rose after 1960, and by the mid-1970s total annual consumption of absolute alcohol per capita was about two gallons, the highest level since the 1830s. Concern over the rising number of drunken-driving-related deaths led to state legislation raising the drinking age to 21 in 1980 and to the organization of Chicago-area chapters of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) in 1987. By the late 1990s, MADD had approximately one thousand members in a five-county area around Chicago (Cook, Lake, DuPage, McHenry, and Will).

Local temperance and prohibition work has also focused on using Chicago's 1934 local option law to dry up sections or locations in the city. For more than a decade Reverend Michael Pfleger, pastor of St. Sabina's, the largest African American Catholic Church on the South Side, led efforts to eradicate “nuisance” bars offering “adult” entertainment and prostitution as well as alcohol and billboards advertising alcohol to African Americans and Hispanics in their neighborhoods. In September 1997 and again in February 1998 the Chicago City Council passed ordinances to ban neighborhood billboards advertising alcohol and tobacco. Reverend James T. Meeks of the Salem Baptist Church in far South Side Roseland also led a working-class and poor African American community's struggle against the overpopulation of liquor stores and bars. In November 1998 voters in five Roseland -area precincts banned alcohol sales. As a whole, Chicago has become drier: in 1998 a total of 468 of the city's 2,450 precincts restricted the sale of alcohol.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.