| Entries |

| C |

|

Cemeteries

|

|

In 1843, a cemetery complex began on the Green Bay beach ridge at North Avenue and slowly extended north with the 60-acre “City Cemetery” and south with the smaller “Catholic Cemetery.” A Jewish Burial Society bought six-sevenths of an acre in City Cemetery in 1846. Four years later, the city added 12 acres to its cemetery by purchasing the adjacent estate of Jacob Milleman, a victim of cholera.

Citing the proximity of the burial grounds to the city's water supply as hazardous to public health, Chicago's sanitary superintendent, physician John Rauch, requested the abandonment of the city cemetery as early as 1858. Burials, however, continued until 1866, when Chicago lost a lawsuit filed by the Milleman heirs, who claimed $75,000 was owed to them as a result of the mistake-ridden sale of 1850. The city chose to move the bodies to private cemeteries located outside of the city limits and return the land to the heirs.

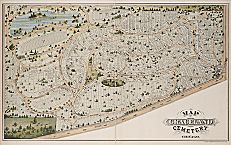

The Great Removal began. City Cemetery bodies were wagoned to Graceland, Oakwoods, Rosehill, and Wunder's cemeteries. The Roman Catholic choices were Calvary in Evanston and St. Boniface in Chicago. Jews had moved their burial ground to Belmont and Clark in 1856.

Chicago city government attempted to prohibit any new burials within the city throughout the late nineteenth century. Yet, as the city annexed additional land, it found itself contending with existing cemeteries inside its limits. Graceland, for instance, was situated two miles north of the city until the great annexation of 1889. The state of Illinois protected these private cemeteries from city bans on burials. Still, Chicago was able to exercise some control over their extension by passing an ordinance in 1931 that made it unlawful for cemeteries to expand or change their boundaries without a special permit.

Regardless of the wranglings over legalities, transportation had already affected interment practices. No longer were burial grounds only a walk away. Suburbs like Forest Park and Niles became available with their “cities of the dead.” The first motor-driven hearse appeared in 1900. As roads improved and distance was no longer a primary locational factor, ethnic and religious groups established new cemeteries. These early necropoli were segregated, exclusive, and excluding. Later immigrants have found space in extant cemeteries, only nominally integrating them. Segregation continues for the dead as well as the living.

All burial space is endangered. The dead continue to stand in the way of the living.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.