| Year Pages |

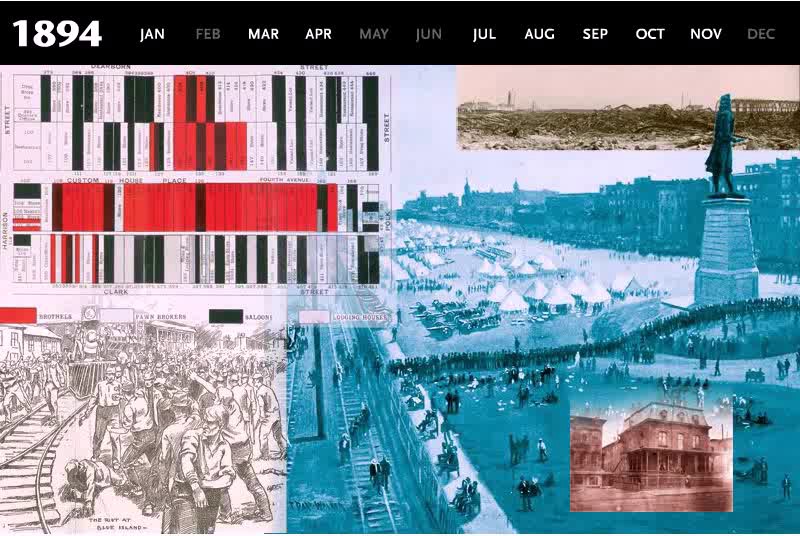

| 1894 |

|

The End of the World's Columbian Exposition in late 1893, coinciding as it did with a severe national industrial depression, let loose destructive forces that shattered Chicago’s grandiose expectations of an unlimited future. Unemployment and misery savagely struck the city. As Jane Addams wrote of her Hull House relief operations, “we all worked under a sense of desperate need and a paralyzing consciousness that our best efforts were most inadequate to the situation.” During the winter, tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs; factories and businesses closed. The unemployed and homeless drifted through the city. In February, the fiery British reformer William T. Stead proposed a new, cleansed vision of the city in his inflammatory book, If Christ Came to Chicago. Based on an 1893 conference that established the Chicago Civic Federation, the book attacked the wealthy, the powerful, the corrupt, and the immoral, often equating the four. Stead’s jeremiad undercut the prestige of Chicago’s builder/philanthropist elite who seemed unwilling to respond to the city’s new social conditions. Their inertia during the Pullman Strike was even more damaging to their reputations. During the months of the strike, the city’s merchant and manufacturing gentry provided little leadership. Rather, they seemed to sink from sentiments of largesse to shudders of fear in a few short months. Like the city, the Pullman Palace Car Company benefited from the fair. Its end, however, brought an abrupt decline to profits. Pullman released workers and lowered wages while keeping rents high in the model town adjacent to the works where employees were encouraged to live. Encouraged by the American Railway Union (ARU), Pullman workers organized union locals and elected a grievance committee. When Pullman refused their demands for higher wages, lower rents, and union recognition, a strike began on May 11. At first, Chicagoans supported the strikers, but when the ARU launched a national sympathy boycott, positions hardened. When local officials seemed unable to control the escalating disorder, president Grover Cleveland authorized the use of federal troops to guard mail shipments sent by train. When troops fired on strikers in Hammond, Indiana, on July 8, attorney general Richard Olney secured an injunction against the ARU, ensuring that the strike would be lost. The violence and disruption of the strike seemed to mark the waning of the power of the city’s former leaders. Together with the depression, it revealed how ill-equipped the city’s institutions were to support the immigrants, industrial workers, and poor. The result was a new agenda for the city, unimagined in either the splendid summary of nineteenth-century culture at the world’s fair or in Stead’s plans for its reformation.

|

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.