| Entries |

| T |

|

Theater

|

|

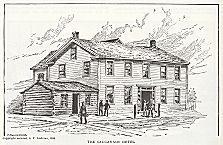

Harry Isherwood co-managed this pioneer ensemble. Though famously dismayed to see a flock of quail crossing a rain-pelted wooden sidewalk on his first morning in town (a sign, he thought, that Chicago was not yet ready for culture), Isherwood and his partner, Alexander McKinzie, nevertheless obtained an amusement license from the city council. They took over the recently abandoned dining room of the Sauganash Hotel, and—sometime in late October or early November—began offering plays, including such titles as The Idiot Witness, The Stranger, and The Carpenter of Rouen. The bill changed every night and the season lasted about six weeks, after which the company went on tour.

|

The ensemble members included Joseph and Cornelia Jefferson and their nine-year-old son, also called Joseph. The child sang comic songs, filled out crowd scenes, and played the Duke of York. He grew up to become one of the iconic performers of his time, a stage comedian widely, intensely, and fondly identified with several roles, especially that of Rip van Winkle. His connection with Chicago is memorialized in the Joseph Jefferson awards, given annually for distinguished work in local professional theater.

The Chicago Theater did not outlast its 1839 season, and Chicagoans went back to relying for the most part on touring shows and circuses. A nonprofessional Thespian Society was formed by local men in 1842 and flourished—according to the story—until somebody stole their sets.

The next great leap took place in 1847, when John B. Rice, newly arrived from Buffalo, New York, contracted with a local alderman to build a theater near the corner of Randolph and Dearborn Streets. Rice's Theater opened on June 28 with a comedy called The Four Sisters in which Mrs. Henry Hunt (later known as Louisa Lane Drew, a founder of the Barrymore dynasty) played all the title roles. According to newspaper accounts, both the play and the place were enthusiastically received.

Rice's Theater attracted major stars of the time, including Edwin Forrest and Junius Brutus Booth. Built of wood, it burned during the summer of 1850 but was replaced within six months by a new brick structure. John Rice sold his theater in 1857 and began a successful political career, serving as mayor of Chicago from 1865 to 1869. Eighteen fifty-seven was also the year McVicker's Theatre opened, under the management of James H. McVicker, an actor and former employee of Rice's who went on to own a chain of theaters in cities around the United States.

|

If the affluent downtown crowds were looking for exotica (not to mention erotica, as purveyed by the likes of Lydia Thompson and her British Blondes, who brought burlesque to Chicago in 1869), the new immigrants in the neighborhoods were longing for something familiar—and found it in their own theaters. A German -language company was operating as early as 1852. Others followed fairly quickly. A Yiddish theater scene developed at the turn of the century and even produced a few mainstream stars. The best-known of these was Muni Weisenfreund, who became Paul Muni on Broadway and in Hollywood. Muni first appeared onstage in 1908, at the age of 13, in a theater his parents operated near the Maxwell Street Market.

|

Although commercial theater flourished in Chicago after World War I, very little of it was local in origin. The city was entertained mainly by touring shows from Broadway. The only consistent exception was the Goodman Theatre, founded in 1925. Indeed the most celebrated theatrical figure of this period was not a playwright, director, designer, or actor but a critic: Claudia Cassidy of the Chicago Tribune earned her billing as Chicago's “dragon lady” in part by attacking the shoddiness of traveling productions.

|

The Chicago Compass lasted only a year and a half, but it led directly to the Second City (1959) and indirectly to dozens if not hundreds of other improvisation-based companies and concepts, both onstage and in other media. It can be considered Chicago's first truly indigenous theater and—after Spolin—perhaps its single most significant contribution to the performing arts.

|

Steppenwolf Theatre arrived a step behind these companies, as part of the off-Loop's second wave, and became by far the most successful of them all. Justly lauded for rough, muscular productions of contemporary American plays—Sam Shepard's True West in particular—Steppenwolf launched (and was, in turn, launched by) the careers of ensemble members such as John Malkovich, Gary Sinise, Joan Allen, and Laurie Metcalf. Though still conceived to be an actor-run theater, as it was when it was founded, Steppenwolf's scope, prestige, and relative wealth have brought it the stature of a regional institution.

In the 1990s the city of Chicago focused on redeveloping the north end of the Loop (appropriately, the area where both the Sauganash Hotel and Rialto once stood) as a theater district. The Goodman relocated to Randolph and Dearborn in 2000, but otherwise the area is tenanted for the most part with corporate theaters offering outsized, elaborate Broadway-cum-Disney-style shows. Third- and fourth-wave off-Loop companies continue to work out of storefronts in neighborhoods throughout the city.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.