| Entries |

| R |

|

Retail Geography

|

|

|

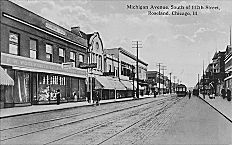

The next crucial development in the shifting retail geography in Chicago was the movement of the Field, Leiter & Co. store from Lake Street to the increasingly fashionable and business-friendly area developing along State Street. The development of State Street as a retailing mecca was aided by Potter Palmer, the Chicago mercantile king, who built an extravagant hotel at the corner of State and Monroe Streets and persuaded the city council to widen State Street. One contemporary observer, acknowledging planning efforts in Paris, referred to Palmer's work as the “Haussmannizing of State Street.” But most important to the retail community in Chicago was Palmer's role in persuading Field, Leiter & Co. to move into a rather ostentatious building on State Street.

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of Marshall Field on retail merchandising. Along with stocking dry goods in the Field, Leiter & Co. store at the corner of State and Washington, Field constantly maintained a stock of high-quality and cosmopolitan products, such as women's handbags and the latest fashions brought over from Paris. Field also helped maintain a loyal customer base through such innovative policies as a money-back guarantee and a competent and reliable delivery service. These customer-friendly policies were complemented by an almost astonishing array of ancillary services, such as children's playrooms, writing rooms, tearooms, and stenographic services. Marshall Field also kept a shrewd eye on the wholesale trade by contracting with the architect Henry Hobson Richardson to design a wholly modern wholesale goods distribution center at Adams and Wells Streets in 1885.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, most of the large-scale retail merchandisers had secured a place on the State Street corridor in the Loop. Along with Marshall Field's, Carson Pirie Scott and other large department stores had large and expansive emporiums that utilized large metal-framed display windows to showcase the wide variety of goods that they offered. Other prominent department stores included Mandel Brothers, the Boston Store, Rothschild's, Siegel, Cooper & Co., and the Stevens stores.

|

In the years before World War II, a new mode of retail geography began to develop in suburban Chicago. Older inner-ring suburbs that were intimately linked to the city by a network of interurbans also developed clusters of retail establishments at junctions of major transfer points. Oak Park followed this pattern quite neatly, with a high concentration of major retailers at the intersection of Lake and Harlem Avenues, including a branch of Marshall Field's. At the same time, many other suburbs were building intricate and elaborately executed retail complexes that catered primarily to people with automobiles. One of the earliest such retail developments in the nation was Lake Forest Market Square in Lake Forest. Designed by the architect Howard Van Doren Shaw and constructed in 1916, this blend of retail and office space with residential apartments offered extensive parking facilities. The other early well-known retail development that catered to automobiles was the Spanish Court in Wilmette. Built in 1926, this innovative development was also built with the understanding that many of its patrons would arrive by automobile.

Despite the increased competition from retail developments outside the city of Chicago, the downtown area maintained its dominant role as a major regional retail center of the first order. Even as late as 1958, it sold 8 times as many shopping goods as the largest regional center within the city (located at 63rd and Halsted) and had 10 times the total retail sales of this particular regional shopping district. While the downtown area maintained its position atop the city's hierarchy of retail centers, the central business district accounted for only 15 percent of all retail sales within the city of Chicago. Many of Chicago's neighborhoods were well served by a nexus of available retail options around major arterials, often including a small department store (such as a Wieboldt's or Goldblatt's) and a variety of other retail businesses.

Planned retail developments became increasingly popular after World War II in the Chicago metropolitan area, though few were built within the city for several decades. One of the most well-known planned retail centers was Evergreen Plaza, located right outside the city limits at 95th and Western. Evergreen Plaza was developed by real-estate mogul Arthur Rubloff, who had initially conceived of such a plan in 1936. When it was finished in 1952, Evergreen Plaza had approximately 500,000 square feet of retail space and 1,200 parking spaces. Cars could easily pull in off the street into the parking lot, and the plaza also featured a conveyor belt that transported groceries from the supermarkets to a parking-area kiosk.

|

In the city of Chicago, many retailers in neighborhoods faced with widespread demographic shifts fell on increasingly hard times throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Former areas of robust retail spending, including many of those on the South and West Sides, found themselves plagued by arsonists, robbery, and a general decline in the socioeconomic makeup of their clientele. The city of Chicago attempted to alleviate the dwindling returns of these neighborhood retail centers by diverting automobile traffic from the main area of pedestrian traffic. While this policy might have been successful in Oak Park (which created a small downtown pedestrian mall in 1974), it was met with resistance and apathy by shoppers and retailers alike along State Street, which was turned into a “pedestrian-friendly” street in 1979 and then restored to traffic in 1996.

Many of the city's formerly vibrant neighborhood retail areas continued on a downward spiral through the 1980s and 1990s. Planned retail developments such as Ford City on the city's Southwest Side seemed to siphon business away from surrounding neighborhoods rather than drawing nearby suburbanites into the area. Large-scale retail developments in the suburbs continued emerging throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, with several notable examples, including the Old Orchard Mall in Skokie and Woodfield Mall in Schaumburg, drawing city and suburban residents. Many of these malls began to offer a diverse set of amenities such as children's playgrounds, valet parking, and senior citizen days.

Another retail development, the “big-box” retail store, began to situate itself within both the urban and suburban fabric in the 1980s and early 1990s. Like many of their historical predecessors, these massive single-story structures were frequently located at significant transportation junctions, such as the confluence of major highways or freeway exits. While big-box retail developments remained popular through the 1990s in the city and surrounding suburbs, the Loop has a seen a new influx of contemporary retailers, many of them occupying prime retail space along State Street. Along North Michigan Avenue, the much-heralded “vertical malls,” such as Water Tower Place, remain popular and highly visible destinations for tourists, suburbanites, and Chicagoans.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.