| Entries |

| B |

|

Block 37

|

|

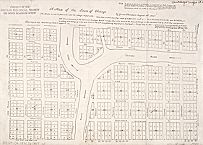

Favored by its unique geography, the land that was to become Block 37 already had a rich history before the first Europeans canoed into the swampy prairie on Lake Michigan. At least 100 years before Chicago was surveyed, scribed, and squared, the Potawatomis pursued an active commercial life on the site. With its proximity to the lake and to the main branch of the Chicago River, the block was important too after Fort Dearborn was established and the area became a key area of settlement of the Northwest Territories.

|

After Chicago's incorporation as a town in 1833, Block 37, situated only several hundred yards from the Cook County courthouse and across the street from the city's largest bank, boomed along with the city. When the Great Fire of October 8, 1871, razed the entire downtown, the block had already been densely developed for decades. Rebuilt immediately after the fire at over four times its original square footage and increasingly added to over the next century, Block 37 shared the fortunes of other American downtowns from New York to San Francisco. Resiliently prosperous and endlessly inventive in the sort of commerce it could support, the block survived not only the fire, but a worldwide Depression and a host of cunning mayors and dealmakers, until it finally fell prey in 1989 to the final “improvement” that flattened, in the name of urban renewal, every one of its buildings—including, without distinction, its architectural treasures and notorious firetraps.

Block 37 was, in the end, a victim of the very trends that it had so efficiently exploited in the past. After the World War II, as Chicago's population began its permanent migration away from the core and out to the suburbs, the block started to suffer from the neglect that would eventually make it a candidate for urban renewal. Beginning in the early 1960s, the historic Loop was bypassed for the redevelopment of North Michigan Avenue. The old downtown was perceived and relentlessly advertised as hopelessly decayed and dangerous. The once superior location of Block 37 at the matrix of the city's political, commercial, and social life now doomed it. By the 1970s, State Street had lost its preeminence as a shopping center to the department stores on Michigan Avenue and to the large regional malls multiplying out in the suburbs. The entertainment “rialto” along Randolph—Chicago's equivalent to Times Square—had closed down its live shows and was subsisting on pornography and action films, while on Washington Street, the gourmet shop Stop and Shop, a city institution, went out of business. Offices for lawyers, political activists, and skilled artisans on the block's Dearborn Street side went unrented as the center of Chicago shifted to the grand new towers of the West Loop. None of the billions of dollars flooding the city during the skyscraper boom of the 1980s reached Block 37 in time.

Ironically, the block's very dereliction became its last chance. Speculators and city hall insiders had written down the land values of the entire North Loop to the point in 1979 when the Chicago Plan Commission declared 26.74 acres, seven full or partial blocks including Block 37, “blighted.” This designation qualified the area for a “taking.” Once valuable commercial property was seized from its lawful owners, condemned, and written down as worthless. After speculators had delayed the taking almost a decade and bid up land costs, the city paid nearly $250 million for the entire North Loop, including nearly $40 million for Block 37 alone. In 1983 a local development group, JMB, won the rights to develop the entire block. A series of delays, beginning with a challenge from historic preservationists and prolonged by costly legal battles, put off the block's demolition until 1989, when the city completely leveled the land and traded the title to the developers for $12.5 million, less than a third of what it had paid. Plans to build two towers and a large retail mall fell prey to the national real-estate crash of 1990. For almost a decade, the block was put to temporary use as a winter skating rink and a summer student art gallery. At the opening of the twenty-first century, this once diverse and active place still lies empty, an unwanted orphan of progress. The history of Block 37 will continue to mirror the rise and fall of Chicago's downtown. Its long and various history is an intimate calibration of the history of a great American city.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.