|

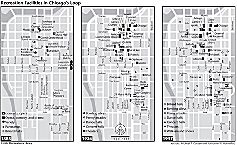

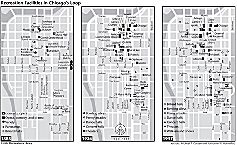

Recreation Facilities in the Loop (Map)

|

Chicago's leisure pastimes have been a product of several factors. Early Chicago's

entertainment

reflected its rough-edged frontier character, but, as the village grew into a walking city, leisure options reflected its growing urbanity. After the

Fire of 1871,

Chicago became an industrialized radial city with a huge, heavily foreign-origin population. These factors had a major impact on working hours, discretionary income, the formation of subcultures differentiated by class, gender, race, and ethnicity, and changing spatial relationships, all of which helped shape the leisure patterns of metropolitan Chicago.

Leisure in Preindustrial Chicago

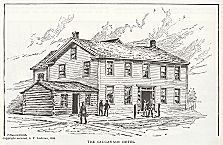

View of Sauganash Hotel, c.1830

|

Recreation in preurban Chicago reflected frontier life. The

Fort Dearborn

community was made up of soldiers,

French Canadians,

and

Native Americans

who enjoyed rural sports,

gambling,

and drinking. They hunted wolves and wild fowl and honed their skills with marksmanship contests. At the time the town was founded in 1833, denizens sleighed, skated, danced, went to

horse races,

and attended monthly concerts of popular music. Mark Beaubien's Sauganash

Hotel

was the most important recreation center in the early 1830s, with dancing, drinking, card playing, roulette, and storytelling.

Chicagoans in the newly established walking city worked six days a week, leaving just Sunday and holidays for rest, most notably New Year's Day, May Day, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. The city charter empowered the municipality to license, regulate, or prohibit entertainment to encourage wholesome recreation, promote safety and morality, and raise revenue. The government originally banned billiards, shuffleboard, baiting sports, card playing, and

prostitution

to discourage

gambling

and restrain the flourishing male bachelor subculture that frequented

saloons,

poolrooms, and brothels, although the revised 1851 charter licensed

bowling

alleys and billiard parlors, while other vile amusements went on illegally. Prostitution flourished. By 1856, 1,000 women worked in 110 brothels. Lotteries were legal, gambling games were commonplace, and betting at the racetracks was popular. A temperance crusade against Irish and

German

drinkers resulted in stiffer licensing and

Sunday closing

laws that culminated in the

Lager Beer Riot.

Chicago & North Western Ad., 1887

|

American middle-class reformers in the 1840s initiated the rational recreation movement that sought to substitute moral amusements for the evil pleasures of the male bachelor subculture in order to uplift people, reduce crime, and improve public health. In 1858 evangelist Dwight L. Moody set up a

YMCA

branch in Chicago to develop muscular Christians. New sports were introduced, particularly

baseball,

a simple team sport that would supposedly build morality, character, and health. One year after the

Civil War,

there were 32 teams sponsored by fraternal organizations, occupational groups, the companies, and neighborhood clubs. Businessmen like Marshall Field, who had earlier opposed baseball as deleterious to hard work, began to see it as a means to promote teamwork, discipline, sobriety, and self-sacrifice, and sponsored company nines. By 1870 civic boosters raised $15,000 for a professional baseball team, the White Stockings (Cubs), to enhance the city's image nationally.

McVicker's Theater

|

Touring professional singers first appeared in Chicago in 1839, the Christy Minstrel shows were popular in the mid-1850s, and the first

opera

season occurred in 1853. In 1837, Chicago's first theatrical performances, starring the renowned Joseph Jefferson, were widely opposed as demoralizing and out of fear that the Sauganash Hotel where they were held might burn down. A weak economy further discouraged

theater

troupes. In 1847 the $11,000 brick Rice Theater was constructed, with patrons segregated by price and race, but it was surpassed by the $85,000 McVickers (1857) and by Crosby's Opera House (1865), with its 3,000-seat auditorium; all three were located in the heart of the city. Popular plays included the works of Shakespeare and Richard Sheridan and productions based on local topics and anti-southern themes.

Colonel Wood's Museum, 1865

|

Other occasional entertainment was provided by touring monologuists and illusionists, exhibitors of panoramas of events like the burning of Moscow, and circuses like Barnum's “Grand Colossal Museum and Menagerie,” which charged adults thirty cents admission. There were also dime museums, whose exhibitions of freaks, wax reproductions of infamous crimes, and objects of historical curiosity were popular with the lower classes.

Ethnic groups had a significant impact on entertainment.

German,

Irish,

and Scandinavian immigrants brought their own amusements, which promoted a sense of peoplehood, especially in terms of language and culture. Germans brought to America an intense love of

classical music.

In 1850, Julius Dyhrenfurth conducted Chicago's first symphonic concert, and in 1852 the Männergesangverein, the city's first male chorus, was founded. An important German theater was established at midcentury that staged German classics that reminded audiences of the Old World. New plays were written that taught how to cope with the New World. The Svea Society (1857) sponsored a Scandinavian theater where performances were often followed by dances. Tickets cost fifty cents.

Beck's American Band, Englewood

|

The Germans and the Irish brought athletic traditions. The Irish emphasized

boxing,

which was part of their own male bachelor subculture and enabled them to fit in with the prevailing bachelor subculture. However, the Germans made a more distinctive contribution with the mainly working-class

turnverein,

which emphasized calisthenics and gymnastics and supported workingmen's interests.

Turnhalles

were community centers, often the largest building in the neighborhood, with a large gym and auditorium. By the 1890s there were 5,000 turners in 34 units, the most of any American city. They provided a model for the establishment of similar organizations by Bohemians,

Poles,

and

Ukrainians.

Leisure in the Industrial Radial City, 1870–1920

Chicago's leisure patterns in the industrial radial era were influenced by industrial capitalism and its social structure, a heterogeneous population divided into ethnic communities, gender, changing spatial relationships, and a liberal enforcement of Sunday blue laws. The upper class had the greatest wealth and control of time. They used leisure activities for fun and social prestige by participating in and financing expensive high-status pastimes. Parties,

clubs,

and sports dominated their social calendar. Charity balls introduced debutantes and honored individuals. Parties were ostentatious multicourse meals at elegant hotels or luxurious mansions. Institutions of high culture like the

Art Institute,

founded in 1879, were established to promote civilization, boost Chicago's reputation, and enhance personal recognition.

Washington Park Race Track, 1903

|

Chicago's elites gathered in the Chicago Club (1869), where men socialized and did business, and the Fortnightly (1873), where women considered social issues and pursued educational topics. Sports clubs, like the Chicago Yacht Club, the Chicago Athletic Club, and the Chicago Women's Athletic Club were less prestigious but enabled its new rich members to gain status and participate in expensive sports. Fascination with English country life and the new sport of

golf,

which was enormously popular in Chicago, resulted in the establishment of suburban country clubs, beginning with the Chicago Golf Club (1893). These organizations were particularly attractive to elite women who enjoyed golf,

tennis,

and parties at the clubs. The elite was very involved in equestrian sports, and a few owned thoroughbreds and belonged to the prestigious jockey club that operated the elegant

Washington Park

Race Track, founded in 1884.

Lake View Cycling Club, 1890s

|

The middle class, which made up 31 percent of the workforce in 1900, generally believed in hard work, domesticity, sobriety, and piety, and wanted to employ free time for self-improvement and self-renewal. Middle-class men worked a five-and-a-half-day week and had sufficient income to pursue leisure activities. The new middle class of professionals and bureaucrats turned to their pastimes to demonstrate their creativity, self-worth, and manliness at a time when WASP birthrates were declining and culture seemed to be feminized by influential mothers and schoolteachers. Men formed organizations that sponsored hobbies like the Chicago Philatelic Society (1886), the Chicago Camera Club (1904), and the Chicago Coin Club (1905). They became active sportsmen, joining groups like the Chicago

Bicycle

Club (1879), and became ardent ball fans. They had the time and money to attend White Stocking games played in midafternoon. The team did not have Sunday games until 1893, originally because of league rules and then because owner Albert G. Spalding incorrectly assumed that middle-class fans opposed public amusements on the Sabbath.

Hockey and Skating, 1903

|

Middle-class women also had substantial leisure time, as they seldom worked outside the home and many had servants to perform household chores. They read

fiction,

belonged to clubs, and shopped in downtown stores. Specialty shops and

department stores

like Marshall Field's made

shopping

an enjoyable experience with tearooms, fine

restaurants,

and free delivery. Increasingly, younger women also participated in sports, encouraged by physicians and female physical educators who recommended exercise to improve health and beauty. Such “feminine” sports as golf, tennis, horseback riding, cycling, and ice

skating

proliferated. Even certain active sports like

basketball

became women's sports, modified by special rules designed to conform to current notions of women's physical abilities.

Arcades on South State, c.1912

|

Low wages and long working hours limited turn-of-the-century working-class leisure opportunities. Less-skilled workers regularly worked 60 hours per week, while more-skilled workers typically worked 54 hours. Yet the limited remaining free time was important, providing opportunities for self-expression, status, and even

politics,

with the

Eight-Hour Day Movement.

Reflecting the immigrant character of Chicago (80 percent of Chicago's population in 1890 was of foreign origin), blue-collar recreation was ethnic, neighborhood, and family-based and tied to religious customs.

Roman Catholic

immigrants observed a Continental Sunday Sabbath, with afternoons free for moderate pleasures that contested local blue laws, while

Jews

observed the Sabbath on Saturdays and considered Sunday a working day. Traditional holidays were still observed, like the

Italian

festivals that honored patron saints in a carnivalesque atmosphere, providing continuity with the Old World. Houses of worship also provided space for weddings, sports, and clubs, most notably the

Catholic Youth Organization,

founded in 1930.

Wading in Union Park lake, 1912

|

Gender was important in socializing and family gatherings that focused on the dinner table. Women prepared traditional foods, and afterwards men and women socialized separately. The primary daily entertainment for working-class women was visiting with friends and neighbors at home, on the stoop, or in the street. Second-generation daughters were very closely supervised, at least until they were full-time wage earners, when they gained a little more freedom. Their brothers, by comparison, had far more liberty to hang out in the

street

or participate in neighborhood recreation. They played sports at ethnic social and athletic clubs, pool halls, bowling alleys, boxing gymnasiums, or

settlement houses,

where reformers sought to use athletics to socialize inner-city youth into the values of the host society.

Steinmetz Saloon, 1898

|

Adult men socialized away from crowded homes at fraternal

clubs

or

saloons,

often the only recreation site in their neighborhoods. By 1915 there was one saloon for every 335 residents in Chicago. German taverns were family institutions, well-lit beer gardens that provided wholesome entertainment. Most others, however, were “poor man's clubs,” highly particularistic institutions where men drank, ate free lunches, played games, and gambled. Irish saloons, for instance, were modest, dimly lit “stand-up” taverns whose customers were encouraged to drink excessively.

Gambling and prostitution were rampant in Chicago. Illegal betting occurred at neighborhood saloons, resorts in the South Side

vice district,

and downtown gambling halls and poolrooms that served as off-track betting parlors. Men of all classes visited houses of prostitution, the most famous of which was the Everleigh House, where an evening could cost $50. The

Vice Commission

identified 5,000 prostitutes working in 1,020 resorts in 1910. When Mayor Carter Harrison II closed the

vice district

shortly thereafter, prostitution moved into residential neighborhoods.

In the 1870s celebrated traveling companies boasting stars like Henry Irving, Ellen Terry, Lily Langtry, and Sarah Bernhardt played the McVicker's, the Academy of Music, and the Grand Opera House, where Chicagoans paid twenty-five to fifty cents to see them.

Vaudeville

made its first Chicago appearance in the 1880s. Immigrants, who often brought with them a theatrical tradition, supported ethnic theaters in spite of weak scripts, inexperienced actors, and a limited audience base. The theater promoted their culture and ethnic pride, gained them respect from the host society, and helped newcomers become acclimatized to America. German theater dominated with

volkstheaters

and classical scripts. The English press reviewed an 1889 performance of Schiller glowingly, and a 1903 performance of Goethe's

Faust

drew 3,600 spectators to the

Auditorium Theater.

Entrance to Ravinia, 1931

|

Musical entertainment flourished between 1871 and 1920. Theodore Thomas first brought his chamber music orchestra to Chicago in 1869 and established the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

in 1891. Certain dates were set aside for workingmen's concerts with reduced admissions. Popular vocal music emphasized light opera, and group singing was common at parties. There was growing interest in opera, and in 1885 over 100,000 enthusiasts attended the Chicago Opera Festival. The 4,300-seat Auditorium Theater, completed by 1890, had its first opera season in 1891 and continued to have opera every year through 1932, when the Civic Opera Company went out of business.

Choral music

was very popular with ethnic groups, especially Germans, Scandinavians, and

Poles.

The three major German singing societies in 1900 consisted of over 200 singing clubs, but interest sharply fell off during

World War I,

when Chicagoans identified German culture as unpatriotic.

Dancing boomed in the early 1900s among all social and ethnic groups. In 1911, an average of 86,000 people nightly attended one of the 275

dance halls

in Chicago, more than went to any other recreation. Especially popular with the most fashionable middle-class couples were cabarets, a type of nightclub influenced by the old beer gardens, public dance halls, and revues. Cabarets combined hot music, new dances, risqué shows, drinking, and smoking.

Freiberg's Dance Hall, 1911

|

Ethnic leaders worried the second-generation would become debauched or meet the wrong people at public dances, so they organized dances at ethnic clubs and neighborhood halls. Their young men and women preferred modern commercial ballrooms with big bands but maintained a sense of ethnicity. They preferred accessible halls where their group dominated or controlled part of the floor. Rather than bringing formal dates, dancers often came in groups or met at the dance. The girls usually danced with neighborhood boys or other fellows from the same ethnic group. Many single immigrant men frequented taxi dance halls where they paid ten cents per tune to dance with women employed by the owner. By the late 1920s, Chicago had 36 taxi dance halls, which, along with cabarets, were often accused of demoralizing young people.

Silent

movies

were a hugely popular entertainment based on a new technology. Chicago's first theaters in the early 1900s were five-cent nickelodeons, simple storefronts in working-class neighborhoods. By 1908 there were more than 340 in the city, and admission had reached ten cents. Moralists' concerns about conduct in the dark theaters and about subject matter resulted in the establishment of a film censorship code by 1909. The cinema boomed in the mid-1910s with the popularity of feature-length movies exhibited in elegant downtown and suburban theaters and accompanied by stage shows and large orchestras.

Plantation Café

|

African American

newcomers welcomed the leisure options available in Chicago which they in turn shaped in important ways. However, African Americans encountered prejudice at theaters, dance halls, YMCAs, public parks, beaches, and other entertainment venues. They had to rely heavily on their own institutions in the

Black Belt

to sponsor recreations and on entrepreneurs who established theaters, nightclubs, and baseball teams. The first notable African American nightspot was the 900-seat Pekin Theater at 2700 South State Street, established by policy kingpin Robert T. Motts to diversify his operations. It became a showcase for black musical talent. A stock company was established to perform dramatics, operettas, and comic operas. Admission was fifteen or twenty-five cents. The leading nightspots in the early 1910s were located on “the

Stroll,

” State Street from 26th to 39th Streets. By 1920 as many as a thousand couples went to the Royal Gardens Café (459 East 31st Street) every Friday to dine, dance, and listen to

jazz

and

blues

music.

Rube Foster, 1909

|

Black ballplayers were barred from playing in organized baseball. While African Americans did attend games played by the Cubs and

White Sox,

most attended Sunday games played by local black semiprofessional teams like the Leland Giants, who were a source of community pride. In 1911 that club was supplanted by Rube Foster's

American Giants,

which became a charter member of the Negro National League in 1920. The team played at Schorling Park (39th and Wentworth), adjacent to the ghetto, where adult tickets cost twenty-five cents.

Other popular commercial entertainments of the time included museums, circuses,

county fairs,

and

amusement parks.

Fairs often publicized agricultural and scientific achievements, most notably the Interstate Industrial Exposition, held downtown from 1873 until 1892. The

World's Columbian Exposition

in 1893 attracted an estimated paid attendance of 21.5 million, who preferred the Midway's attractions to displays of technology or art. Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show that summer played before 6 million spectators on a 14-acre site just across from the main entrance to the fair.

Sans Souci Amusement Park, 1908

|

Major amusement parks included White City, established in 1905 at 63rd and South Park Way and emphasizing low-class pleasures like carnivals, bowling alleys, and a roller rink and roller coaster. By 1914 it provided year-round entertainment including two dance floors that accommodated five thousand people. It was partially destroyed by a fire in 1927 and went into receivership six years later. Riverview (1904–1967) was the North Side equivalent, with thrill rides, freak shows, dance halls, and a beer garden.

A much-needed park system was funded by the legislature in 1869. The new large parks were

Jackson

and

Washington,

south of the city; Douglas, Central (

Garfield

), and

Humboldt

on the West Side; and

Lincoln Park,

the largest, at the city's northern border. These suburban parks, at first accessible only to middle-class residents of nearby communities and train riders, originally emphasized receptive recreation. But park goers wanted active recreation, and in the 1880s baseball diamonds and tennis courts were constructed. Lakefront beaches were opened for public use after 1895. Park space was also set aside for the Garfield Park

Conservatory

and the

Lincoln Park Zoo.

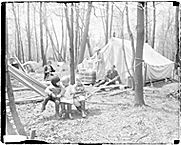

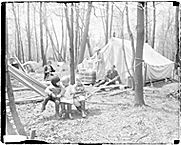

Camping in Forest Preserve, 1922

|

Unfortunately, the system lagged behind population growth. In 1899 one-third of the population lived more than a mile from any park. The suburban parks in the 1890s had become more accessible to better-paid workers once carfare on the expanding streetcar system dropped from fifteen to five cents, yet this was still too expensive for the poor. Reformers organized a small-park movement in the 1890s to alleviate the inner-city's need for play and breathing spaces, leading to the municipality funding neighborhood parks in 1904. The

Plan of Chicago

of 1909 stimulated future recreation by recommending the extension of Grant Park and the building of beaches, Municipal

(Navy) Pier

(1914),

forest preserves

(1914), and lakefront museums.

Leisure in the Interwar Era, 1920–1945

In the 1920s the average Chicagoan enjoyed a higher standard of living than ever before. By 1920 the blue-collar workweek had shortened by about 10 hours compared to 1914, plus wages had appreciated significantly, averaging about $1,000 a year for unskilled workers and $2,000 for skilled. During the

Great Depression

incomes plummeted, and workers enjoyed a lot of unwanted free time. The national standard of a 40-hour workweek was established in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act.

In the 1920s leisure was heavily influenced by the greater freedom of young women who smoked, drank liquor, wore short dresses, danced the Charleston, and dated men with automobiles that provided privacy for dating couples as well as greater access to suburban recreational opportunities. During this decade ethnic peer groups mediated mass culture through sponsored dances, clubs, and sports. But by the 1930s white industrial workers were generally

Americanized,

and the ethnic factor was less prominent, although clubs, parades, and holidays were (and remain) significant.

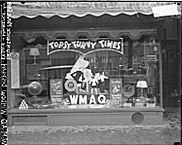

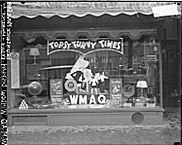

Topsy Turvy Times Display, 1926

|

There was a growing reliance on commercial entertainment by the 1920s. Blue-collar workers spent on average $22.56 a year on movies, more than the middle class and more than one-half of their amusement budget. Neighborhood theaters competed with downtown movie palaces with cheaper admission, films that reflected community tastes, and larger playhouses primed for a middle-class audience. In 1921 the city's largest cinema was the 3,000-seat Tivoli Theater (Cottage Grove and 63rd), which had a marble lobby and charged $1 admission. Sound was introduced in 1927, within three years all the big theaters had sound. Sound altered the ambience at neighborhood theaters, where audiences that in the silent era had been pretty loud quieted down to hear the actors. There was a movie seat for every nine Chicagoans during the Depression, when movies took in about one-third of all entertainment expenditures. Neighborhood prices for adults ranged from fifteen to twenty-five cents, half the price of downtown theaters. Sound films hurt the once-flourishing legitimate stage, which barely survived the early Depression, mainly with Broadway shows.

Radio became ubiquitous during the 1920s. Eighty percent of programming presented musical shows and comedy sketches. Nonprofit ethnic, religious, and labor stations supplemented commercial stations. The Radio Act of 1927 promoted station consolidation but did not kill ethnic programming, which in the mid-1930s accounted for 5 percent of local

broadcasts.

Families bought Victrolas, often on credit, so they could play their favorite music at home. Sales of

ethnic music

swelled as Italians bought records of Caruso singing operas,

Mexicans

purchased recordings of Mexican music, and African Americans bought “race” records made by jazz and blues artists.

Regal Theater and Savoy Ballroom, 1941

|

Nightlife flourished in the 1920s despite

Prohibition

and the demise of the workingmen's saloon. Illegal drinking became an exciting middle-class pastime at speakeasies. When Mayor William Dever closed many clubs in the mid-1920s,

roadhouses

in

Cicero,

Stickney,

and

Burnham

that offered liquor, sex, and gambling replaced them. Exotic “black and tan” nightclubs in the

South Side

ghetto, like the “Plantation Cafe,” offered integrated audiences excellent music and the thrills of being naughty and dangerous by drinking illegal liquor, dancing to hot jazz, and rubbing shoulders with celebrities or gangsters. The center of the ghetto's nightlife shifted from the Stroll to 47th Street, where the first large commercial dance hall for African Americans, the Savoy, was opened in 1927, followed two years later by the 3,500-seat Regal Theater. These were a part of the “chitlin' circuit” of black theaters in the United States. Forty-seventh Street was home to the big bands in the 1930s and 1940s and

rhythm and blues

music in the mid-1950s.

Northerly Island and Lagoon, 1933

|

Chicagoans relied heavily on public resources for entertainment, particularly sites envisioned by the 1909

Plan of Chicago.

The

Field Museum

moved in 1921 to

Grant Park,

and next door the $6.5 million

Soldier Field

was opened in 1924 and completed five years later along with the John G.

Shedd Aquarium

and, a year after that, the

Adler Planetarium.

Soldier Field was the site of the 1927 Dempsey-Tunney rematch, seen by 104,000, and the 1937 Austin-Leo high-school football championship, attended by over 110,000. In 1933 the

Museum of Science and Industry

opened with popular presentations of scientific and industrial subjects. Museum attendance dropped off sharply during the Depression. Field Museum crowds dropped by one-third between 1933 and 1936, with 90 percent coming on free days. An exception was the

Century of Progress Exhibition

of 1933 and 1934, which drew 40 million people. In 1934,

Brookfield Zoo

opened, and 22 different

park districts

were merged into the 5,416-acre Chicago Park District comprising 84 parks and 78 fieldhouses, along with golf courses and swimming pools.

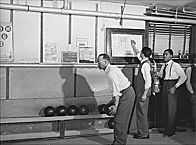

South Side bowling alley, 1941

|

The sports boom of the 1920s fell off during the Depression. The Cubs were a popular attraction, winning four pennants from 1927 to 1938; the

Bears

began playing at

Wrigley Field

in 1921; and the

Blackhawks

began playing in 1926 at the Coliseum, moving to the Stadium three years later. Boxing and horse racing were legalized in 1926, and several tracks soon opened, including Arlington Park in 1927. Participatory sport also expanded. There were 55 metropolitan golf courses, including elite clubs whose initiation fees cost from $3,000 to $5,000. Bowling alleys and billiards halls boomed among the working class until the Depression, when one-third of the former and one-half of the latter closed.

Leisure in Metropolitan Chicago since 1945

St. Joseph's Beach, c. 1940s

|

The leisure activities of postwar Chicago were influenced by the same variables as in earlier periods, particularly a rising standard of living, along with technological innovations, fashions and fads, age, race, gender, and homesite. Two-day weekends were the norm along with increased

vacation

time. By the 1980s, Chicagoans were spending about 6 percent of their income on leisure, double the 1901 proportion. Class became less important, although differences in taste remained significant. The upper middle classes who lived in fashionable neighborhoods like

Lincoln Park

and

Hyde Park

and the wealthier suburbs were the main clients at theaters, concerts, golf courses, and college football games. Lower-class Chicagoans devoted relatively more attention to such sports as baseball, boxing, and horse racing, and to TV, whose rise hurt movies, radio, and reading. Race played a big factor, with differences in musical tastes and nightlife. Racial discrimination hindered opportunities, reflected by uneven park development in different neighborhoods. The feminist movement that emerged in the 1960s encouraged women to work, secure higher-paying jobs, become sexually liberated, and participate in sports, a sphere from which they had been largely absent since the early 1900s.

Blue Note Jazz Club, c.1950s

|

Chicago enjoyed a rich nightlife, which flourished in the 1950s on Rush Street at

nightclubs

like Mister Kelly's and at South Side blues halls which declined with the coming of

rock'n' roll. In the 1970s most of the remaining old clubs died in the wake of disco, urban decay, and the expense of booking name entertainers. Blues revived in the 1990s with new clubs on the African American South Side and especially with trendy North Side locales like

blues

and Kingston Mines. Jazz had a big following with places like the Green Mill in

Uptown

and the London House (360 North Michigan Avenue), a showcase for Ramsey Lewis, Oscar Peterson, and Stan Getz. Chicagoans had a choice of many comedy clubs, most notably the

Second City.

Eating out became an important recreation in the 1960s, with ethnic restaurants for the budget conscious as well as fine dining. Since 1980, Chicagoans have combined their love of music and cuisine in the annual Taste of Chicago lakefront festival.

High culture prospered in this era. In 1953 the

Lyric Opera

was organized, restoring a tradition of outstanding opera and, with the Chicago Symphony, making the city an internationally renowned center of classical music.

Dance companies

and especially theater proliferated. By 1998 Chicago was home to about 50 theater companies, from community and experimental theaters and suburban dinner playhouses to

Loop

theaters that charged Broadway prices for Broadway-style productions.

Oak Street Beach, 1960

|

Interest in participatory and spectator sport has grown substantially. Especially since the 1970s, Chicagoans have taken advantage of public beaches, bicycle paths, volleyball courts, and

soccer

fields to improve

fitness

and to socialize. In the decades from the 1950s through the 1970s, the Blackhawks regularly sold out the

Chicago Stadium,

and attendance at racetracks, Bears games, and major league baseball rose, the latter abetted by extensive TV coverage and the ambience of

Wrigley Field.

Interest in basketball was mainly at the collegiate level until the

Bulls

became popular in the 1970s and achieved fanatic support once they became title contenders in the late 1980s. The cost of attending sport events, however, rose dramatically in the 1990s, making them unaffordable for many Chicagoans.

Conclusion

Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, 1994

|

Chicago's leisure patterns have been historically influenced by the city's growth and maturation. Leisure opportunities were a product of economic development, which shaped the social structure, income levels, and available free time and surplus income, on the one hand, and, on the other, of urbanization, which reshaped urban space and was accompanied by a booming population. Leisure patterns were further affected by entrepreneurs who commercialized recreation, by politicians who promoted public parks and festivals, and by immigrants and southern African Americans who brought with them their own cultural traditions and values.

Steven A. Riess

Bibliography

Cohen, Lizabeth.

Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939.

1990.

Gems, Gerald R.

The Windy City Wars: Labor, Leisure, and Sport in the Making of Chicago.

1997.

Riess, Steven A.

City Games: The Evolution of American Urban Society and the Rise of Sports.

1989.

|