|

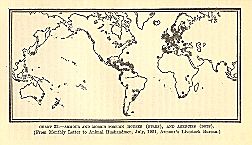

Chicago's World (Map)

|

For most of human existence no city existed on the southwestern shore of

Lake Michigan.

Chicago arose there within the thinnest sliver of human time. But having been willed forth, Chicago became a prototypical American product, built from scratch and in a hurry, a timeball of urban dreams a mere 175 years old. And well before its own centennial, in its precocious size, itchy dynamism, and rough edges, Chicago had become what Frank Lloyd Wright called the “national capital of the essentially American spirit.” As Chicago's material presence and power have grown, a parallel world has arisen to shape the outlook of its citizens, the reach of its physical prowess, and the outer bounds of its influence.

This essay maps that world by considering Chicago's role within the territorial economies of its region, the nation, and the globe, as well as its cultural institutions, intellectual creativity, and projected identity. Chicago redefined its spheres of influence, both internal and external, in five distinct but related stages.

New World Coming: 1780–1832

Map of Northwest Territory

|

“Chicagou” came to life as one of several meeting points linking the diverse habitats of the

Great Lakes

with Indian portage routes to the vast Mississippi Valley. A nexus of periodic trade for centuries among Indian peoples, it acquired new meaning as European explorers, fur traders, and adventurers pounced on its regional advantages. As the

fur trade

swelled in the late eighteenth century, Chicago formed as a loose community of Indian,

French,

and American traders distinguished by their long-distance ties, biracial households, and pragmatic cohabitation. It was a society dependent on consumer demand a continent and an ocean away, yet its isolation bestowed congenial self-governance upon its members.

Silver Brooch, c.1799-1800

|

This multiethnic world came under pressure from advancing colonial interests, reflected in the strategic establishment of

Fort Dearborn

in 1803. As the fur trade declined and American settler interest grew, the small but relatively successful integrated community quickly succumbed to the relentless influx of white frontier opportunists intent on quickening the trade in European commodities and transforming the Middle West into a farmer's paradise. This world had no place for indigenes set in their ways.

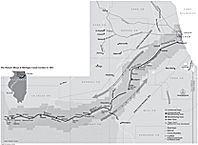

Merchant Coming: 1833–1848

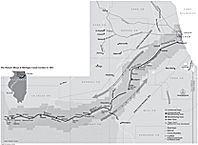

Illinois & Michigan Canal Corridor (Map)

|

The city of Chicago was born on the promise of a canal capable of providing cheap transcontinental water access from

Lake Michigan

to the Illinois River, and whatever additional transport links might then follow. The

Illinois & Michigan Canal

had a difficult birth, spanning a quarter century of planning, funding, and construction. Unlike the Erie Canal, Chicago's 97-mile-long waterway was built through a virtually unpopulated region, ahead of demand. Yet the canal's very imminence spurred settlement along its margins and brought hoards of speculators and capable businessmen to its Chicago terminus, many from New England and New York, with much-needed eastern capital in their pockets. Not surprisingly, then, Chicago's commercial links during the wait for the canal were primarily with the northeastern states of the Union. Most traffic came by lake, though intrepid travelers also journeyed overland through southern Michigan and northern Indiana.

Letter from Dixwell Lathrop, 1835

|

A strange geometry of external relations paired this economic and cultural link to the east with political power emanating from the southern sections of Illinois, home to the governor and legislative influence over internal improvements. Little did these politicians realize how geographically lopsided the long-term benefits of canal construction would be, although Abraham Lincoln rightly stressed that any benefit for northern Illinois would indirectly aid the rest of the state. Had state representatives further south known how astounding Chicago's growth would be during the quarter century to follow, and how fatefully it would etch the social and political divide between the city and “

Downstate,

” they would surely have hindered the canal's completion. As it was, Chicago at first developed as a terminal lake port awaiting the opening of transport avenues to the west and south, already savoring the prospect of huge increases in interregional trade. The immense confidence in the future shown by Chicago's fast-accumulating entrepreneurial class spurred speculative

real-estate

bubbles of unprecedented scale, and this confidence spilled over into other

business

activity.

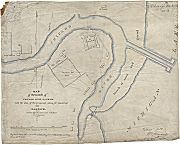

Plan for Mouth of Chicago River, 1830

|

The

built environment

of Chicago combined an odd mixture of boomtown flimsiness and incipient solidity. The former could be seen in the countless utilitarian homes and stores constructed of wood—going up by the score daily—while the latter characterized the proud new government structures, such as the courthouse, customs house, post office, and several elegant churches. Chicago built itself in the image of eastern cities of the day, full of Greek revival

architecture

and tall spires, as well as Federal-style commercial blocks that would have looked at home in Boston or Philadelphia. It was a merchant's town, focused on the business core strung along both sides of the main stem of the

Chicago River

and benefiting from the federal government's financial help in straightening the river's mouth. Considering that the state canal commissioners (who controlled all canal land sales in the city environs) drew up and implemented the city plan—together with the canal works themselves, the river improvements, and the

infrastructure

provided by the establishment of federal services—one could be excused for regarding early Chicago as quite the government town. Such priming of the pump, together with the rush of private capital from outside, ensured the city's future.

Chicago possessed no clear urban margin. Land sales and lot

subdivisions

were so lusty and widespread that houses and businesses tapered off indiscriminately into the countryside. Yet the place was too small and pedestrian-based to have suburbs. Chicago grew to more than 20,000 residents by 1848, a burgeoning community of new arrivals and transients preoccupied with getting and spending. Institutional development proceeded slowly, with a tilt toward commerce, especially among the

newspapers.

Self-made men built mansions filled with imported exotica. More complete cultural refinement would come later.

Galena & Chicago Union Station, c.1849

|

For all the tenuous new wealth, when the canal opened and the first short railways were constructed, the physical world of Chicagoans was still decidedly local. The range of travel within a 24-hour period confined travelers to a sphere that barely penetrated the Illinois Valley and the southern districts around the base of Lake Michigan. The year 1848, however, was pivotal. The canal and first railroad west brought sudden agricultural bounty to the city from this new hinterland, and Chicago prospered as a transshipment center. This led to the formation of the Chicago Board of Trade and subsequently to its system of futures trading on wheat and corn deliveries.

Balloon frame construction,

strikingly associated with Chicago, forever changed Americans' access to inexpensive homes, and other auguries of an innovative urban environment began to make their appearance. Chicago had begun to define itself as a Midwestern metropolis, not just an Eastern reproduction.

Industrial Coming: 1848–1894

Railroad Pattern in 1950 (Map)

|

While the canal triggered Chicago's take-off to sustained growth, the concentration of long-distance

railroads

during the 1850s, '60s, and '70s gave the city its regional power within the national economy. The railroads permitted Chicago to surpass the longer-established and proud city of St. Louis for control of trade in the great continental interior and the Far West and underwrote a dramatic industrialization of the metropolis that placed it at the forefront of American modernity by century's end. St. Louis was not the only rival; Chicago also eclipsed the older Queen City of Cincinnati and hobbled the chances of contemporary rivals such as Indianapolis and Milwaukee. St. Louis had seemed perfectly situated to serve as the central transfer point for the continental nation, but it was Chicago instead that fully grasped its own potential as the hub of western land routes and the industry-friendly water routes of the Great Lakes to the east. The radiating of trunk railroads from Chicago in all directions by the 1890s brought all manner of business to the city and gave its residents unparalleled choice in connecting with other places, making it a national center both economically and culturally. Chicagoans could now reach the bulk of the continental United States within 24 hours, a boast no other city's boosters could make.

The 1890 U.S. census listed Chicago as the country's second largest city (after New York), a fact surely attributable to Chicago's commercial ascendancy, but also to its strategic

annexations

of surrounding

townships

during the year prior to the census. This happy conjunction of affairs was not unimportant in securing the epochal

World's Columbian Exposition

for Chicago a mere two years later.

Illinois Steel at Calumet Harbor, c.1890

|

What the annexations only underscored, however, was the rapacious industrial development that Chicago and its outlying satellite communities had attracted by the 1890s. From the

agricultural machinery

industry (embodied by McCormick's reaper firm) of the late 1840s, to the giant

meatpacking

sector (the Armour and Swift companies) that emerged from the

Civil War,

and the manufacturing of complex machinery and railroad equipment (at George Pullman's Palace Car Company, for example) in the 1880s, Chicago industrialized on a gigantic scale. The economics of steelmaking came to favor a two-way system of

iron

and

coal

exchange through the Great Lakes shipping network that diffused the industry from Pennsylvania to the Middle West and to Chicago in particular. Railroads and steel undergirded a broad industrialization that transformed Chicago from a merchants' town into a metropolis of heavy industry with all its job-creating implications. Chicago became a factory city simultaneously for producer and consumer goods, which it could distribute in all directions. In 1848, Chicago had been dependent for most of its sophisticated manufactured goods on eastern imports; by the 1890s, Chicago competed with eastern centers in most categories of mass production. It was also becoming a

banking

center of national importance.

Economic Origins of Communities (Map)

|

Physically, Chicago in this period developed a star pattern set within a giant wheel of satellite settlements. First, industrialization created a commuter city, a web of residential enclaves bordered by a latticework of industrial corridors, all woven together by mass transit sinews that thrust the city outwards in vectors along commuter railroad lines and selected

streetcar

routes. The railroads gave birth to bedroom suburbs strung like beads along lines out from the central city. These commuter spokes of the metropolitan wheel connected with outlying towns (

Waukegan,

Elgin,

Aurora,

Joliet,

and

Gary

) that had industrialized in their own right. Suburbs born on a grand scale were functionally dependent on Chicago in all but local governance, and outlying cities came within Chicago's daily orbit. A centripetal metropolitan world pulsating on a daily basis had begun to emerge.

Montauk Block, c.1880

|

The Great

Fire of 1871

propelled Chicago's urban core into a modernizing mode. The center would be built with immense solidity (balloon frame wood construction had all too easily become kindling) and, increasingly, to a great height as tall buildings became technically feasible and businesses came to favor their operational efficiencies and symbolic potential. The core also gained culturally, as civic and business leaders began to create an institutional structure for arts, science, and letters through the founding of permanent performing companies (e.g.,

Chicago Symphony Orchestra,

1890), libraries (e.g.,

Newberry Library,

1887;

Chicago Public Library

and

Crerar Library,

1897), museums (e.g.,

Field Museum,

1894), and universities (e.g.,

University of Chicago,

1892) to humanize somewhat the raw face of this upstart behemoth. What kept the metropolis raw were the gross inequities of large-scale capital in an age of robber barons getting rich from abundant cheap labor sometimes made to work in scandalously unsafe conditions. The worker unrest of 1886 and the

Pullman Strike

of 1894 were explosive highpoints in a long struggle between labor and capital in Chicago that paralleled and punctuated its rise to industrial might.

Second Coming: 1894–1968

Armour/Morris Foreign Houses, 1924

|

Chicago's meteoric rise to replace Philadelphia as the nation's second largest city conditioned Chicagoans to expect their city to catch up with and surpass New York in short order. And it was not simply a matter of uncontrolled boosterism. Using a heartland-rimland model of urban supremacy in the deployment of natural resources, a University of Chicago geographer confidently predicted just such an outcome in a 1926 address before the

Commercial Club of Chicago.

While his predictions were not accurate, they reveal a recognition of the power of massive industrialization to propel the metropolis forward in size and complexity on the basis of coal, steel, and (later) petroleum. For the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, Chicagoans believed in the unfailing virtues of mass production in centralized facilities in central locations, and shaped their city to proffer these conditions. Chicago became the great western anchor of a vast heavy-manufacturing belt stretching from Massachusetts to Illinois. To the west, north, and south lay the immense resource regions to supply it with raw materials—corn, wheat, cattle,

lumber,

iron ore, coal, and petroleum—with Chicago as consumer and funnel to eastern markets, as well as dispenser of manufactures to these staple-producing regions. From 1900 to 1970, Chicago functioned as a complete national-scale metropolis, with particular sway over a continental interior extending to the Rocky Mountains and beyond. By 1950, Chicagoans could travel to four continents in a single day's journey, thanks to planes and trains. New York had more international ties and better links with the national hinterland when only one extra-local connection was needed, but Chicago was its only serious competitor and trying hard to cut the margin.

Origins of Foreign-Born Population (Map)

|

Chicago's world was enlarged socially, too, by the diversifying regions around the world from which it drew its new population elements. A ceaseless procession of new migrants piled into Chicago's growing factories. Eastern and Southern European immigrants streamed through East Coast ports of entry and headed straight for the capital of the midcontinent. Subsequently,

African Americans

headed north in unprecedented numbers from the penury of southern cotton fields. All added to an already multicultural city long dominated by

Yankees,

Irish,

and

Germans.

For some from overseas, such as the

Swedes,

Lithuanians,

and

Danes,

Chicago became the second city for their ethnic community in the world, a veritable exclave of emigrants with new lives and new allegiances.

The world Chicagoans created in the region during this long period of industrial hegemony was characterized by rising densities in developed districts, infilling between the spokes, and aggressive expansion into the urban fringe, pushing it back until the metropolitan wheel became more like a giant crescent extending inland from the lakeshore. As the suburbs proliferated, an antiurban bias pitted them increasingly against the central city, socially and politically. The spread of the automobile offered individual freedom, until the next encounter with gridlock. Superhighways were inserted into the metropolitan frame, disrupting community life in the tight neighborhoods where

expressways

were pushed through, while creating wholly new axes for urban development beyond the built-up zone.

Travel and Transport Building, 1932

|

Chicago flowered in this period as a center of literature,

art,

design, and performance. From the novelists of the early-twentieth-century

Chicago literary renaissance

to the rise of Chicago

blues

music, from the advent of the

Art Institute

to the rise of

opera,

ballet,

and the popularity of

theater,

Chicago invented, presented, and reconfigured its feisty urban culture to the world. Through boom and depression, peace and war, expansion and segregation, this cultural awakening created a canon of works that reflect the energetic, convoluted, contested social worlds of the time and something of the identity of the place. Above all, Chicago projected a hunger for and celebration of modernity, best captured in the technological wonders of the 1933

Century of Progress Exposition

and the continuous record of architectural innovation from the earliest steel-skeleton

skyscrapers

to the Miesian lessness of slab-style architecture that culminated in the totemic Prudential Insurance Building.

But it was a fractured modernity, tolerating racial injustice, housing segregation, job discrimination, and political demagoguery. Urban

planning

came of age, became bureaucratized, and, despite successive clarion calls for collaborative regional visions (beginning most notably with Daniel Burnham), stopped, stupefied, at the municipal boundary. As suburbs prospered on Federal Housing Authority mortgage subsidies and became increasingly diverse in vision, social character, and environmental appeal, the central city inherited all the problems of an aging infrastructure, threatened tax base, and divided people. Moreover, the connected city was also the visible city: the 1968 Democratic National Convention gave the world an eyeful of America's social cleavages and provided a glimpse of Chicago's unsettled world.

Global Coming: 1969–2004

Joliet Iron Works Historic Site, 2005

|

The world has been globalizing for centuries, but only since the 1970s has electronic connectivity gone meaningfully global for businesses and individuals. In this human environment, with its boundless competition for resources and markets, cities must strive to be global in their connections, if not always in assets and urban reputation. Chicago ranks with New York and Los Angeles as one of the world's 10 “alpha” cities in most inventories of global economic hipness. This status has been earned through a combination of old-fashioned, cumulative development of economic and social infrastructure critical to international operations, as well as through painful readjustments in the last three decades of the twentieth century to metropolitan deindustrialization, particularly severe in the central city. While industrial loss afflicted the “Rustbelt” as a whole, Chicago emerged tolerably well to compete in a new environment of diversified, globally positioned, high-tech industries, as well as to develop its financial and corporate services institutions. While losing much of its banking independence, Chicago sought to buttress its role as a home to international corporate headquarters. New York far outdistances Chicago in this field, but the move of the Boeing Company to Chicago in 2001 suggested the city's continuing viability at the highest levels of global business support.

In a world in which individuals can communicate via satellite signals with others almost anywhere in the world, the reach that a traveler can personally extend around the world in 24 hours remains a measure of social and societal significance. In 2000, such a traveler from Chicago could penetrate all six settled continents (although by no means reach all other important cities). Air travel has become an American norm for global and interregional movement, and Chicago's possession of strategic and busy (sometimes too busy)

O'Hare International Airport

has been key to its global connectedness.

O'Hare Dedication, 1963

|

Whether or not Chicago has reached a stage of “postmodernity,” the metropolitan crescent has become an ever-farther-flung web of regional settlement. Exurbs—residential subdivisions sitting amid cornfields with no visible support from nearby urban services—scatter across the countryside one hundred miles from downtown Chicago and send commuters to the outer fringes of the metropolitan employment web. Frequent direct daily express bus service connects residents of Madison, Wisconsin, and central northern Indiana with flights leaving from O'Hare Airport. Five million suburbanites inhabit the margins of Chicago, which struggles to retain and add to its own three million residents. This world is one of ever greater anonymity, congestion amid sprawl, efforts to maintain costly infrastructure, and strangely skewed or nonexistent conversations among communities, political and cultural, in the metropolitan web, as parochial worlds seek distance from one another's problems.

As Chicago's suburbs have aged, the central city has learned at least some lessons in re-capitalizing the built environment. Something of a renaissance has taken hold in Chicago's public governance, approach to services, and official outlook on city viability and livability. That renaissance has been driven at least in part by

demographic

changes that occasionally transform minorities into majorities. But it has also been driven by a certain discipline imposed by global competitiveness to put on an attractive face for visiting conventioneers,

tourists,

and other contributors to the urban economy. The city has become festooned with wrought-iron fences, median planters, and other elaborate street furniture, as well as spectacular nighttime lighting effects on tall buildings and other landmarks.

Gentrification

and new-town-in-town developments have penetrated large swaths of the once-tired urban core, crossed racial lines, and received municipal support through tax abatements and the effective

privatization

of neighborhood street parking.

Retrospect

Chicago's world has expanded exponentially over time, in physical, psychological, symbolic, and practical ways. The metropolitan “neighborhood” of greater Chicago has more people crammed in and strewn about than ever before; they move about with greater speed and frequency; there are vastly more things to acquire and aspire to; there is more choice of what to do and what to be interested in—and greater difficulty in comprehending the complexity of it all. Psychological time and distance and the pace of life have been redefined many times. Contemporary Chicagoans are worlds away from their predecessors, even those just a few generations back. Could Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, the I&M Canal Commissioners, Marshall Field, Jane Addams, Theodore Dreiser, and Anton Cermak possibly have imagined the character of Chicago as it existed at the opening of the twenty-first century? How much more difficult is it to realistically imagine the Chicago world they inhabited?

Michael P. Conzen

Bibliography

Belcher, Wyatt Winton.

The Economic Rivalry between St. Louis and Chicago, 1850–1880.

1947.

Goode, J. Paul.

The Geographic Background of Chicago.

1926.

Mayer, Harold M. “The Changing Role of Metropolitan Chicago in the Midwest and the Nation.”

Bulletin of the Illinois Geographical Society

17.1 (1975): 3–13.

|