| The Plan of Chicago |

| Chicago in 1909 |

| Planning Before the Plan |

| Antecedents and Inspirations |

| The City the Planners Saw |

| The Plan of Chicago |

| The Plan Comes Together |

| Creating the Plan |

| Reading the Plan |

| A Living Document |

| Promotion |

| Implementation |

| Heritage |

|

In its eighth and last chapter, the Plan provides a useful six-point summary of its key recommendations:

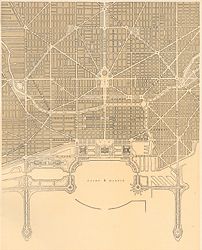

1) "The improvement of the Lake Front," notably the building of a shoreline parkway and the development of Grant Park, as Burnham had advocated since the mid-1890s;

2) "The creation of a system of highways outside the city" in the form of concentric semicircular roadways, the outermost of which would loop from southeast Wisconsin to northwest Indiana;

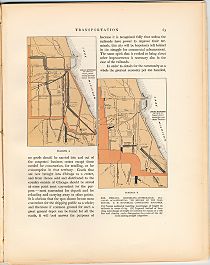

3) "The improvement of railway terminals," mainly by locating them along Canal and Twelfth Streets at the edges of the current downtown, and "the development of a complete traction system for both freight and passengers," consisting of trains, tunnels, elevated rapid transit, and subways that would enable freight shipped through Chicago to bypass the center of the city and make the arrival and departure of passengers in this area more efficient and convenient;

4) "The acquisition of an outer park system, and of parkway circuits," continuing the work the Outer Belt Commission began in 1903;

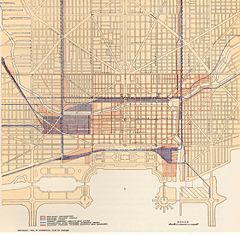

5) "The systematic arrangement of the streets and avenues within the city," including the cutting of new diagonal streets and the widening of important thoroughfares, "in order to facilitate the movement to and from the business district";

6) "The development of centers of intellectual life and of civic administration, so related as to give coherence and unity to the city," notably by building new homes for the Field Museum and Crerar Library near the Art Institute in Grant Park, and by constructing a mammoth civic center of government buildings at the intersection of widened Congress and Halsted Streets. (The Crerar Library, privately endowed but open to the public, was established in 1897. At the time of the Plan, it was located in the Marshall Field building.)

|

Approaching the Plan

To reduce the Plan of Chicago to a list of points risks overlooking the luxurious experience of reading the lavish volume and also missing the underlying conceptions about Chicago it presents. As carefully thought out as it is, the Plan of Chicago makes its first appeal to the senses, not the mind. Like many of D. H. Burnham and Company's buildings, it exudes a forthright and foursquare gravitas. This is literally true, since it measures twelve-and-a-half inches high, ten inches wide, an inch and three-quarters thick, and it weighs in at over five pounds. The book's title and the ornate cipher of the Commercial Club are impressed into the cover in gold, and its cream-colored pages are gilded on the top and rough trimmed at the edges. The Plan of Chicago is not a mere book but a tome, whose proper pedestal is a mahogany board room table tastefully polished to a dull sheen. It presents itself as something to be admired as much as understood.

|

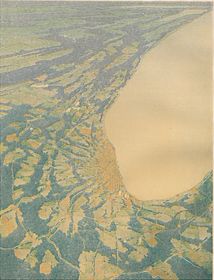

This impression continues once one reverently opens the Plan. An elegant note in the front matter informs the fortunate reader which of the limited edition of 1,650 copies he or she has the honor to hold. Opposite the title page is the first of Guerin's renderings. While the subject of this illustration is immediately identifiable as a bird's-eye view of the southwest reaches of Lake Michigan meeting the settled prairie, the vantage required to see the enormous expanse on display is so celestially high that the curvature of the earth is visible. Earth and water strike the eye less as physical features than as epic masses. The print on the title page conveys a sober momentousness. The three years over which the Plan was prepared, as well as the date of publication, are solemnly announced in Roman numerals. Though it speaks of the future, the volume presents itself as a monument.

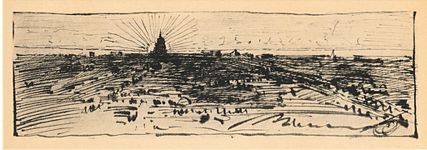

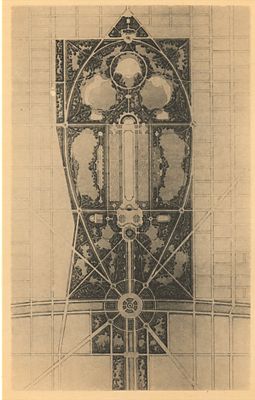

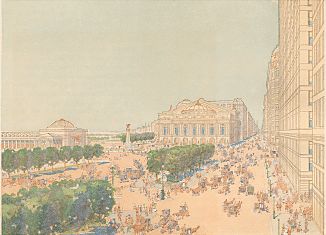

Given the Plan's portentous presence, one's first impulse is not to settle in and see what it has to say, but to leaf respectfully through its disciplined gorgeousness, focusing first on the dozens of illustrations that dominate the 124 pages of the main text. In so doing, the viewer—not yet quite the reader—enters a kind of alternate world. As noted, there are very few views in the Plan of contemporary Chicago. The illustrations instead invite us to lose ourselves in wonder at the Chicago the planners dare us to imagine. Janin's hushed black-and-tan elevation of the Civic Center folds out to reveal a vision of an ideal neoclassical cityscape dominated by an elongated dome forty or more stories high that dwarfs the other dignified structures supporting and surrounding it. Guerin's skill with a limited but expressive range of color—from pastel beige and blue to sunny yellow and green to deep violet and brown—and with perspective leads us into a more serenely civilized place than we have ever known.

|

|

|

|

Even once one sits down to absorb the import of the words that occupy the spaces between the illustrations, the Plan takes its time in getting to its ostensible subject. The presentation of specific proposals does not begin until the third chapter. The first two chapters prepare the reader's mind by explaining why planning is necessary and then describing in broad strokes what effective planning means. The opening chapter, "Origin of the Plan of Chicago," traces the steps leading up to the Plan, from the Columbian Exposition to the Commercial Club's decision to conduct a study that would suggest improvements in "the physical conditions of Chicago as they now exist." The second chapter, "City Planning in Ancient and Modern Times," highlights the traditions to which the Plan is heir, celebrating Paris as the planned city par excellence. Finally, in the next five chapters, the proposals arrive. They appear in a general geographical progression from the periphery of Chicago to its center: encircling highways, transportation systems, and downtown. The book concludes with a discussion of the Civic Center, which the text deems, in an architectural metaphor, "the keystone of the arch" that is the Plan.

|

To look for a strictly logical order in the Plan of Chicago can be misleading and disappointing, however. Its proposals are not always laid out systematically, the prose is redundant in places, and while the chapters frequently provide much information, it sometimes is a little hard to grasp exactly what the Plan is recommending. In addition, although the book is without question finely produced, sharpness of detail is not a priority in the Plan' s images. Even the photographs seem impressionistic rather than documentary, and the illustrations are suggestive rather than definitive. While they are carefully drawn and in several cases accompanied by explanatory legends, they are often difficult to decipher, however much they engage the eye. The text does not help much, since it rarely refers to the images. An exception is the brief mention of the dome of the Civic Center, but even here the Plan insists that it "does not seek to impose any particular form on structures." In another place, when the Plan is talking about transportation, it states that it is just picking some logical and natural routes. The planners would leave it up to engineers and other experts to determine the optimum location for this or that improvement. They would trust architectural schools and societies to come up with designs.

|

This odd element of diffidence in such a bold and ambitious document perhaps blunts the common criticism that the Plan's authors—or at least the illustrators—seem to ignore or reject Chicago's place in the forefront of modern architecture, established in significant part by the many large and distinctive commercial and public buildings designed by Burnham and Root or D. H. Burnham and Company. Guerin often replaces Chicago's actual variegated cityscape with block upon block of uniform structures. The criticism is very well taken, though the intention behind much of the Plan's imagery seems to be to enlist the reader in a cause, not to offer faithful depictions of contemporary Chicago or precise blueprints of what might replace it. It is extremely unlikely that the planners wished to tear down the structures that Burnham and other leading Chicago architects had designed, though they would have been happy to remove many others. The broader aim of the Plan, including Guerin's drawings, is to render its readers receptive to the notion that Chicago might in fact be made a place more beautiful and fine than anyone previously thought possible if they would only embrace the vision the Plan advances.

Assumptions and BeliefsOf what does this vision consist? The specific recommendations the Plan offers are based on a set of governing ideas. The foundational assumption is at once the most optimistic and audacious. The planners above all believed in the malleability of history in general and of urban experience in particular. More specifically, they had faith in the ability of a self-appointed elite like themselves to recreate urban space and, as a result, expand the human prospect within that space. In the Plan, they present themselves in terms characteristic of many turn-of-the-century reformers, not as a selfish special interest or as idle dreamers, but as "disinterested men of wide experience" who are indisputably well qualified to produce something good enough to "commend itself to the progressive period of the times." They confidently maintain that the Plan "conceals no private purpose, no hidden ends," but a "determination to bring about the very best conditions of city life for all the people."

|

Part of this determination involved convincing others that what some might consider irreconcilable goals were in fact mutually reinforcing objectives. As Paris proves, the Plan argues, a modern urban center like Chicago could possess convenience, functionality, beauty, and even dignity—a term it employs several times. The Plan admits that its proposals might seem unrealistic to skeptics, but it insists that they are practical. When the planners advocate rationalizing the location of railway passenger terminals and freight transfer depots and reducing water and air pollution, for example, they declare that bringing order and convenience to Chicago would be neither impossible nor even expensive. But "haphazard and ill-considered projects," not to mention dirt, would be terribly costly since they threaten human health and drive both working people and the wealthy away. Creating order and turning a profit are congruent rather than conflicting aims. In regard to rearranging transportation in the city, the planners state, "With things as they should be, every business man in Chicago would make more money than he does now."

The Plan employs both mechanistic and organic figures of speech to describe the better Chicago it promotes. On the one hand, the Plan declares that it is possible to make the city what it calls "an efficient instrument for providing all its people with the best possible conditions of living." On the other hand, it speaks of the downtown as "The Heart of the City," the title of chapter 7. The text retains this capitalization in subsequent uses of this term.

|

The heart metaphor implies that Chicago has a life force that derives from and emanates through the setting and the people who live there. Reflecting on the natural features that define the Chicago region, the Plan implies that the sheer scale of lake and prairie places upon local residents the obligation of greatness. In less fortunately endowed places, "man and his works may be taken as the measure," but in Chicago "the city appears at that portion of illimitable space now occupied by a population capable of indefinite expansion." The metaphor also expresses the Plan's contention that it is important to think regionally on at least two levels: first, by understanding the natural relationship between Chicago and the hinterland beyond; and, second, by keeping in mind the vital connection between the downtown and other parts of the city.

Chicagoans had to confront the current challenge they faced, the Plan tells them, by mustering their political and financial support behind its proposals. The final chapter reminds the reader that two short generations ago the city was barely a village. Since that time it had lifted itself out of the mud, fashioned a park system, mounted a world's fair, and reversed the flow of the river. All of these were both practical and aesthetic achievements. Similarly, while the planners' proposals might seem to be beyond the financial resources of Chicago, they in fact would take economic advantage of the city's existing natural and man-made features. Besides, these proposals could be realized without seriously increasing the existing tax burden, since the growth that they assured would bolster credit, lift assessed values, and stimulate the production of yet more wealth.

|

What was now required, the Plan states, was that the city's responsible elite lead the campaign for change. In the section of the sixth chapter that discusses the lake and prairie as defining Chicago as a place without limits, the Plan of Chicago comes closest to the rhetoric of the famous dictum attributed (though never definitively) to Burnham, "Make no little plans." It announces:

|

At no period in its history has the city looked far enough ahead. The mistakes of the past should be warnings for the future. There can be no reasonable fear lest any plans that may be adopted shall prove too broad and comprehensive. That idea may be dismissed as unworthy of a moment's consideration. Rather let it be understood that the broadest plans which the city can be brought to adopt to-day must prove inadequate and limited before the end of the next quarter of a century. The mind of man, at least as expressed in works he actually undertakes, finds itself unable to rise to the full comprehension of the needs of a city growing at the rate now assured for Chicago. Therefore, no one should hesitate to commit himself to the largest and most comprehensive undertaking; because before any particular plan can be carried out, a still larger conception will begin to dawn, and even greater necessities will develop. |

Words of Warning

|

While the Plan of Chicago is almost relentlessly upbeat, some passages do express warnings and doubts about urban life, especially if the proposals advanced by Burnham and the Commercial Club do not win support. Like the Plan as a whole, such passages appealed primarily to businessmen who had much at stake in Chicago's future. The closing words of the second chapter remind readers that the experience of other cities ancient and modern, abroad and in the United States, "teaches Chicago that the way to true greatness and continued prosperity" depends on keeping the city convenient, healthful, beautiful, and orderly. "The cities that truly exercise dominion rule by reason of their appeal to the highest emotions of the human mind," the Plan declares. This assertion is posed not by way of inspiration, but as a "problem" Chicago must solve.

A few pages later, the Plan puts specific blame behind the general charge that the same lack of regulation that perhaps once encouraged growth was now stifling Chicago. It takes to task the "speculative real estate agent" and "the speculative builder," who shortsightedly spread blight by trying to squeeze the last cent of profit out of every investment. In the "Heart of Chicago" chapter, the Plan discusses the need not only for widening Halsted Street but also for sanitary reform of industry and housing situated near Halsted's intersection with Chicago Avenue, an area beset by smoke, soot, pollution, and filth from trains, tanneries, garbage dumps, and coal docks. The Plan anticipates one of the more unfortunate methods of post- World War II urban renewal when it recommends cutting broad thoroughfares through "this unwholesome district" as a way to improve it. It also calls, more ominously, for "the remorseless enforcement of sanitary regulations" that would guarantee airier, brighter, and cleaner buildings.

The Plan implicitly condemns here what it sees as the dangerous excesses of capitalism, a system with which the Commercial Club was certainly allied. The Plan speaks with surprising directness of the city's need and right to place limits on speculators and land owners. It does so not only when it states that the lakefront "by right belongs to the people," but also when it defends the public appropriation of real estate needed to widen streets and to eradicate threats to sanitation and health. "It is no attack on private property," the Plan contends, "to argue that society has the inherent right to protect itself against abuses." If society does not exercise this right, the planners warned, it might be necessary to resort to socialism in some form. Chicago, unlike London, has not yet reached the point at which the city must intervene and provide housing for people living in unacceptable conditions. Unless timely action was taken, however, the Plan predicts that "such a course will be required in common justice to men and women so degraded by long life in the slums that they have lost all power of caring for themselves."

|

There are moments when the Plan even raises the possibility that city life is by its nature degrading to all people, not just the helplessly impoverished. Wage earners and even the well-to-do need access to parks because "density of population beyond a certain point results in disorder, vice, and disease, and thereby becomes the greatest menace to the well-being of the city itself." "Natural scenery," on the other hand, "furnishes the contrasting element to the artificiality of the city," a refuge "where mind and body are restored to a normal condition, and we are enabled to take up the burden of life in our crowded streets and endless stretches of buildings with renewed vigor and hopefulness." These remarks perhaps reflect the influence of Frederick Law Olmsted on Daniel Burnham, and they recall the anti-urban sentiment behind Burnham's decision to raise his children outside of Chicago, by the woods and lake in bucolic Evanston. "He who habitually comes in close contact with nature," the Plan observes, "develops saner methods of thought than can be the case when one is habitually shut up within the walls of a city."

The discussions of slums and parks state the planners' belief that a person's surroundings significantly determine his or her behavior. Time and again, the Plan maintains that terrible living conditions diminish the individual and, by extension, the entire city, and so should be of concern to the prosperous as well as the less fortunate. It speaks of the slums on the Near West Side as a "cosmopolitan district inhabited by a mixture of races living amid surroundings which are a menace to the moral and physical health of the community." There is as much alarm as sympathy in such passages. At times the Plan seems to advocate, as some reformers did, removing poor city children from their squalid home life and, by implication, from the negative influence of their parents, to places where they could be taught higher morals and values, that is, the standards by which middle- and upper-class Chicagoans presumably lived. It advocates constructing attractive public school buildings and playgrounds, so that "during all the year the school premises shall be the children's center, to which each child will become attached by those ties of remembrance that are restraining influences throughout life."

|

Such passages reflect the authors' view that one of the many purposes of city planning was control of the urban masses. While the Plan of Chicago's central theme is how best to deal with rapid change in one of the most dynamic cities in the world, it is a remarkably conservative document that hopes to infuse in the public at large a belief in the status quo, in the social and economic hierarchy in which the planners were at the top. To give Burnham, Bennett, and the Commercial Club due credit, they were sincere in their civic-mindedness. They backed their rhetoric with their time and their money, serving on the boards of any number of charitable and social services agencies. Whatever their own blind spots, they were generous in their instincts and critical of the selfishness of some of their peers, realizing that any plan worth the name had to deal with the needs of the entire population.

At its most idealistic, the Plan tries to conceptualize just how that population could truly be a coherent urban community. The talk of the slums being a "cosmopolitan district inhabited by a mixture of races," as well as the observation made on the Plan's very first page that the chaos of rapid growth was complicated by "the influx of people of many nationalities without common traditions or habits of life," indicates that the native-born Protestant men of the Commercial Club worried about the difficulty of finding common ground in Chicago, especially on their terms. They hoped that their Plan would unify Chicagoans by inspiring civic pride and loyalty in an urban society that provided health, prosperity, and happiness to all those fortunate enough to dwell there.

|

It is no wonder, then, that the Plan saves its discussion of "The Heart of Chicago" for chapter 7, the last one that describes particular recommendations. The argument that it advances here for making Congress Street "a thoroughfare which would be to the city what the backbone is to the body" reveals a simultaneously hopeful and desperate desire for stability and order in unstable Chicago: "Thus, and thus only, is it possible to establish organic unity, and, in connection with the improvements of the streets above mentioned, to give order and coherence to the plan of Chicago." The Civic Center, as the Plan conceives it, would be comparable in its effect on Chicago to that of St. Peter's or the Forum on Rome, the Acropolis on Athens, or the Piazza San Marco on Venice. It would be, that is, "the very embodiment of civic life." If the Plan of Chicago's proposals are realized, its authors promise, "The Lake front will be opened to those who are now away from it by lack of adequate approaches; the great masses of people which daily converge in the now congested center will be able to come and go quickly and without discomfort; the intellectual life of the city will be stimulated by institutions grouped in Grant Park; and in the center of all the varied activities of Chicago will rise the towering dome of the Civic Center, vivifying and unifying the entire composition."

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.