Nelson Algren

|

Amorphous as it may be,

water

has shaped both urban experience and urban imagination. Just as

Lake Michigan

and the rivers and creeks of the Chicago region have flowed through the work of writers from

Willa Cather

to Nelson Algren, the city's architects and planners have found water an inevitable factor in envisioning the city as an emodiment of civilization, art, and economy.

Washington Square Park

|

Water also has a concrete ubiquity in city life. Its clear physical manifestations embody our best hopes, from minimum standards of access to water and sanitation to the joys of public parks and open spaces. However, water also exemplifies the failure of those aspirations, drawing our attention to polluted streams, inadequate plumbing in substandard housing, and disparities in access to aquatic recreation.

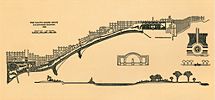

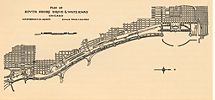

Plan of Chicago, Chapter 6, Unnumbered (Plate 107)

|

As an economic resource or an amenity, water has seldom been allowed to remain in its natural state. The

built environment

includes a means of moving water up and down, in and out. Water is pumped into urban structures, and then out again; it flows through outdoor fixtures like fountains and ponds. Existing waterfronts have been reshaped and reimagined as urban places not just for traditional economic purposes (harbors or factory sites), but also as esplanades, boat launches, and bathing beaches. Water in cities is not wholly unnatural, but it is a hybrid. Even recreation and

leisure

landscapes seldom let nature reignurbanites deliberately have shaped and reshaped nature to meet their needsor their desires.

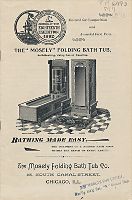

Advertisement for the Mosely Folding Bath Tub, 1893

|

Chicagoans first pumped water from municipal systems into their homes in the 1850s. Like their counterparts in other cities, they probably were far more aware than we are of the water and sewers that make indoor plumbing possible. Cities across the U.S. and Europe developed water distribution systems, at first to guard against fire and disease and then quite quickly to meet urbanites' demands for stationary baths, toilets, kitchen sinks, laundry tubs, and showers. By 1885, Chicago residents spent $2,500,000 on indoor plumbing in their new houses, connected to growing water and sewer networks. At the time of the

Civil War,

only the wealthiest Chicagoans could afford the luxury of indoor plumbing. But with each passing year, plumbers became more adept and efficient at their work and manufacturers mass-produced more and more of the pipe, fittings, and fixtures. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the new kitchens and bathrooms of the Chicago

bungalows

(and the contemporary brick two-flats) sported the latest plumbing fixtures, now affordable to the working class. By the 1930s, the conventional availability of indoor plumbing led the federal government to identify housing as substandard if it did not have indoor plumbing within the unit. In less than 75 years, what had once been a luxury had become a necessity of modern American life.

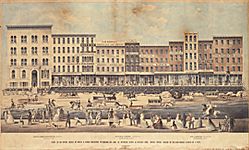

The location of houses in relation to water in Chicago also follows a pattern shaped by economic change and socioeconomic inequality. In the 1840s and 1850s, many of Chicagos poorest residents lived adjacent to the

Chicago River.

Many toiled on nearby public works projects that were reshaping the urban landscapethe

Illinois and Michigan Canal,

the harbor improvements, the widening and dredging of the Chicago River, and the

grade raising

that lifted Chicago out of the mud.

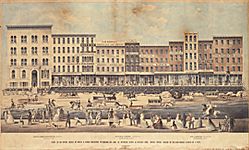

Street raising on Lake Street, 1855

|

These laborers had little money and often built shanties on land held by speculators. At the time, those with the means to own property had little interest in residing on the land. The Chicago River and adjacent low-lying areas harbored disease. During the cholera epidemics in the late 1840s and early 1850s, cases were concentrated along the river and among the

German,

Irish,

and

Norwegian

squatters who died in their houses near the river. Property holders lived further from the river on higher ground.

Plans for Julia Lathrop Homes (formerly Diversey Housing Project)

|

The concentration of poverty along the river wards continued well into the twentieth century, as riverfront areas suffered disproportionate exposure to

industrial pollution.

Cabrini-Green

and the Julia Lathrop Homes of the

Chicago Housing Authority

were sited along the river in the 1930s and 1940s. This trend began to change in the mid-twentieth century, as deindustrialization, sewage treatment, and the initial effects of the

Deep Tunnel project,

led to dramatic improvements in water quality. Beginning with Marina Towers in 1964, luxury housing began gravitating toward the Chicago River for the first time in the citys history. The demolition of the Cabrini-Green Homes, and their replacement with mixed-income residential developments, indicates the profound economic shift in riverfront housing.

Fountains and channels of the World's Columbian Exposition, 1893 (looking south across west end of basin)

|

By the late nineteenth century, water as a backdrop for a beautiful city extended beyond homes to gardens, parks, and preserves. Frederick Law Olmsted assigned a prominent role to water, as he designed plans for the South Park system and the romantic suburb of

Riverside.

Olmsteds design for

Jackson Park,

along Lake Michigan south of 55th Street, tamed the natural

dune

landscape into a bucolic green park alongside the lakes beaches.

Wetlands

were drained into sculptured ponds that served as a backdrop for scenic walks and drives. The

1893 Worlds Fair,

located in Jackson Park, presented an even more deliberately designed

landscape,

with water as a central but certainly not natural backdrop. Building from his experience with the Worlds Columbian Exposition, Daniel Burnham crafted a 1909

plan

for the region that put a shaped water landscape at its center. Along with Edward Bennett, Burnham planned for one long lakeshore park within Chicago, as well as recreational development of the Chicago River. Their vision shaped the transformation of Chicagos lakefront in the twentieth century, as landfill created a string of public parks, harbors, and roadways.

Plan of Chicago, Chapter 1, Pages 6,7

|

|

The development of large and small public parks and preserves across the region was closely tied to Lake Michigan shoreline as well as to the rivers and streams across the region. Many of these sites were developed in the late nineteenth century as commercial leisure spaces. Private beaches and picnic groves catered to working-class Chicagoans, while more affluent residents purchased large tracts of land for vacation spots. The development of public beaches and picnic groves in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries countered this trend, but hardly brought equal access to recreational waters. Racial segregation prevailed, even on public beaches, into the early twentieth century, leading to clashes such as the one that sparked the 1919

Race Riot.

Beginning of the 1919 Riot

|

Urban neighborhood and suburban residents have also used water to foster community. Over the past century, city and suburban governments have built pools, bike paths,

ice skating

rinks and

boating

facilities far from natural waterways, reflecting the imagination of Chicagoans as they use water to reshape their urban world.

Ann Durkin Keating

Bibliography

Greenberg, Joel.

A Natural History of the Chicago Region.

2002.

Keating, Ann Durkin.

Invisible Networks: Exploring the History of Local Utilities and Public Works.

1994.

Solzman, David.

The Chicago River: An Illustrated History and Guide to the River and its Waterways.

1998.

Hill, Libby.

The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History.

2000.

|